I’m having a mastectomy in the morning. My left breast is going to be removed – completely. In a few hours from now, you may legitimately refer to me as The One Tit Wonder. Although I wish my husband was alive to love me through it, I also know that my ability to perform a soapy tit wank will be temporarily suspended, so he definitely had the best of me, and I should probably welcome the timing. Since I’m going to spend the rest of the year with one boob, a dry vagina (apparently one of the main side effects of my forthcoming hormone treatment) and bald from chemo, I doubt that I am the North of England’s Most Eligible Widow at this point, anyway. I’ll be holding him in my heart through all of this, if not in my cleavage.

I’m finding all this pretty hard to take, but I know it has to be done. I also know that, had I just gone ahead and booked myself in for a mastectomy with immediate reconstruction back in August when I was diagnosed, I might have already woken up a few months ago, cancer-free and with a new breast. But, I panicked. I couldn’t come to terms with having cancer less than four months after losing my husband to the same vile disease, and delayed, and tried to do anything I could to save my boob. But it didn’t work, and the three little Stage One tumours they thought I had are actually one large, late Stage Three tumour – in my skin, my chest wall, and my lymph nodes. What couldn’t really kill me before, now absolutely could.

The day before I went for nipple and breast-saving surgery, a friend of mine died from metastatic breast cancer. And I know that, with or without her boob, her family would give anything to have her right back here. That’s exactly how I feel about my husband, and I’ve written about it many times before. In his case, he lost his oesophagus and part of his stomach, but he was here, and I loved him. And now he’s not there (but I still love him, and miss him desperately – as do our young sons.) He could have had a leg or an arm or even his willy removed, and I really wouldn’t have cared. Well, I might have cared if he hadn’t had a willy, but we’d have coped. He was so much more than one single part of him could ever have been.

I didn’t think it could happen to me. It doesn’t happen that way, does it? Kids sometimes lose one parent to cancer, but not two within months of each other. Well, it bloody well does happen. I’m lucky – I’ll survive this, with a fair wind and a decent cocktail of drugs, and provided they take off the right tit. (By which I mean the left tit. Please, God, make sure they take the left one.) Later, I’ll have a new one, but I’ll have to live with a bra full of sponge for the time being, because they tell me there’s no point in rebuilding something that’s going to be damaged by radiotherapy, and I must wait until everything settles down. I even have my little pink bag of shame packed inside my hospital case, with a regulation-issue mastectomy bra and a wad of sponge for me to add to or take away from as I see fit, when it’s all done. I fucking hate it already. My tits are brilliant. Were brilliant. I don’t want to swap one of them for a fucking sponge.

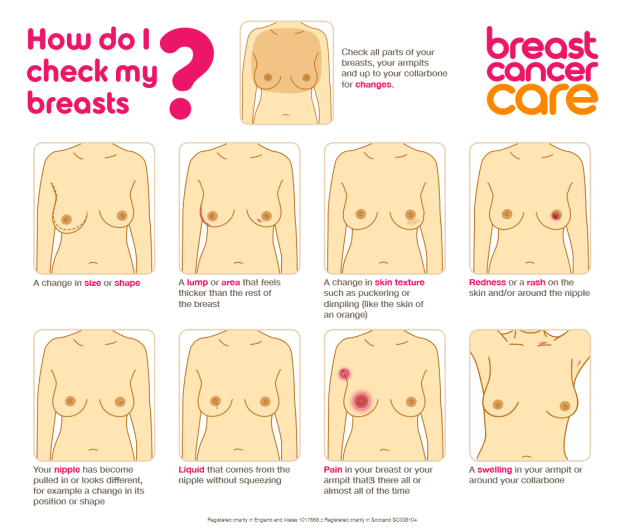

So, what I want to say to you is this. Feel yourself. Go on. You’ll feel a bit of a twat, especially if you end up at the doctor’s, but don’t worry. If you think you’re lumpy, or spot any changes, just go and get yourself checked. Doctors aren’t magicians; they’re only human, and it took me three visits to be finally diagnosed. Medicine can be quite hit and miss, but you’ll definitely miss if you don’t go in the first place. Don’t be embarrassed. Doctors have their fingers up people’s arses on a daily basis, so what makes you think yours is so special they’ll remember it? Ask Dr Google and make your web search history even more interesting. Know the signs. Whether it’s your boobs, your bowels, the top of your leg, or the end of your penis, it really doesn’t matter. It shouldn’t have happened to me, but it did, and my dithering and flapping and grief could have cost me my life. My husband and I both told the doctor as soon as we’d noticed symptoms, and in my husband’s case it was still curable, but only just. Oesophageal cancer is impossible to spot until it becomes hard to swallow, by which time it’s often too late, but we still had an extra precious year thanks to him acting when he did. Hopefully, we’ve got mine in time. So, seriously – what’s the worst thing that could happen? You’ll die. That’s what.

I live every day with two little boys who cry and scream and fight their way through the heartbreaking consequences of terminal cancer, and I owe it to them not to let them see me through it as well. It might be slightly embarrassing to go to the doctor, but believe me – the process of death is far worse. No matter what happens – whether you have life-saving surgery, or you end up in a hospice – you’re going to have strangers faffing about with catheters, so make sure they’re doing it to keep you alive, and not just to make you comfortable. And if you’re fine, you’ll be relieved, and there won’t be any catheters at all. If I’d been in an accident and the only way to save me was to saw off my leg, they’d have done it there and then and asked questions later. I have to remember that this is the only way. I wish my husband had only lost an extraneous body part, and not his whole life, because by losing him we lost everything that made us a family.

It was never the right time to let go of my husband, and it’s not the right time to say goodbye to my left boob. But, I have to remember that it’s only a tit. My husband thought it was fucking ace, and we did have some fun with it and its counterpart over the years. Most importantly, though, it fed and nurtured our children, and if I let it go now, I can continue to do that for many years to come.

Love Fanny x

A useful infographic from http://www.breastcancercare.org.uk. Go on, have a feel. You know you want to. And when you’ve done that, check everywhere else. Visit http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-symptoms for more information.