People say “I just CAN’T imagine.” A lot. They say it a lot. I think I’m quite good at hiding what I’m thinking (which is WELL FUCKING TRY) with a shrug and a smile, and a “that’s OK. I hope you never have to,” because I really do. When they inevitably stroke my left arm in solidarity (it’s always the left one,) I let them, even though I don’t really know if I’m supposed to stroke theirs back, because I’m awkward and British, and I’m not entirely sure what stroking my arm will do to aid my husband’s return to life anyway. But it probably makes them feel better, and I’m OK with that. I’m sure I’d do the same if the tables were turned. What in the name of fuck DO you say?

People are really nice. I know they can’t imagine, because I can’t either, and none of this is quite how I thought it would be. It still isn’t.

Following any shitty medical diagnosis, people often describe a “new normal.” It’s not the life we’d planned, but eventually you get to grips with the chemo regimes or hospital appointments or where the best coffee is within a stone’s throw of the treatment centre (don’t go to the canteen – it’s shit,) and you build a new routine around it, or in our case, our entire working week. I remember, when my husband was first diagnosed (when it was curable – OH no it wasn’t!) imagining him about to spend months on end as an in-patient, shrivelled up and bald, when in reality – for the first three cycles at least – life was relatively normal except for the odd bit of retching into a bowl and a Number One on top. We went places, did stuff, and lived our lives. And he carried on working. Self-employed and uninsured, you see.

The difficulty ramped up, slowly but steadily. After the oesophagogastrectomy (or, “the op,” which is less of a mouthful,) he needed more careful handling, but life carried on and the boys got used to seeing him replace his jejunostomy feed at breakfast while they filled their cereal bowls. The feeding tube came out. He went back on chemo. The retching became worse, and he went bald again. He didn’t sleep at night and nor did I, but we carried on. Things got shittier, but we kept going. We kept working. We kept bringing up our kids, and loving each other, and pissing each other off. We kept going for two years, until he stopped.

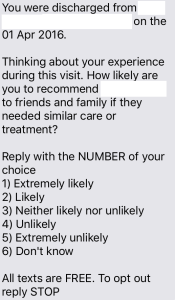

When my husband was given two weeks to live, he was relieved. He’d thought he had hours. I’d been called in to the hospital urgently, late on a Friday afternoon to “discuss his scan,” and was told that the doctor would stay behind to see me. I asked if I should bring the children, and they said not yet. That was a fairly hefty clue that something was amiss, although it was April Fools’ Day, so there was a glimmer of hope. My husband held my hand. He wiped my tears, and asked me to promise just two things. He wanted to die at home, and he asked me not to let him die alone. I gave him my word.

He then went on to say that a Bag for Life would probably be an unwise investment at that point.

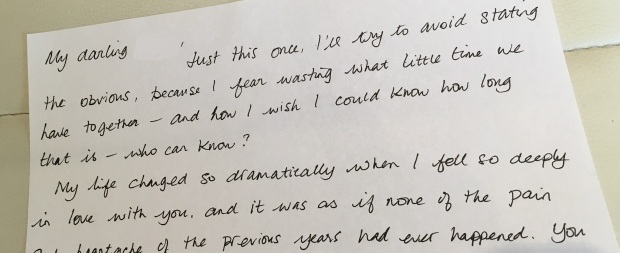

The few days after he came home from hospital, and before he’d lost his mind, we quickly shut down our business. He wouldn’t rest until I’d contacted all our clients with his “permanent non-availability”, as he called it, and sent the invoices out. The fucking invoices. Who gave a shit? He did. He needed to know we could afford to take some time off, so he could relax. And die. It felt as if we were about to go on holiday. In fact, by then, we were on holiday. We were at home, but not working. We ignored the phone. It was, somehow, lovely. We chatted. We held hands. Friends and relatives came over, but knew not to stay too long. He asked for a sign on the front door asking for visitors by appointment only, because the constant ringing of the doorbell was driving him mad, although some people ignored it anyway. I kept that fucker up for weeks after he’d passed. Some people still ignored it.

The day he died, I don’t think I knew he was going to. I don’t honestly think I ever thought he would. A friend had stayed in the spare room so I wouldn’t be alone and frightened on my makeshift bed beside my husband if he started to die in the night. He said good morning to her and asked after her husband, his friend. I don’t know what he said after that, but it was idle, mixed-up chitchat. There were no meaningful last words. He probably vaguely asked for a cuppa. He slept. The hospice came (for the first time, after a fortnight of chasing) to give him some nursing care, and a wash and a fresh t-shirt. They looked after him; he was clean and moisturised, and his teeth were brushed. I suppose, in hindsight, he was ready. I texted the vicar to say that I was worried he had barely moved and didn’t seem well, but didn’t hear back and thought nothing of it. I was too busy sitting by his side and listening to his iPod on shuffle (or “Dad FM” as he preferred to call it) and skipping past any songs he wasn’t keen on. No point in wasting whatever time he had left being forced to listen to shit music.

The boys came home from school; they popped in to say hello, saw Dad was asleep, and wandered back over the road to play with their friend. My husband’s best mate, our GP, called in after surgery to see how things were, as he always did, and said gently that he thought today may be my husband’s last. I put the kettle on and chose not to believe him. He offered to stay the night, but Marie Curie were supposed to be coming to night-sit for the first time, and I thought they could damn well do their bit at last. We returned to the sitting room where my husband was sleeping. His head had fallen to one side and his skin was grey. I thought he’d died, and was devastated that I’d broken the one last promise I’d been determined to keep – that he wouldn’t die alone.

Then, he breathed. I looked up to see our friend in tears, my husband still alive, and our boys out of the house. I didn’t know how long we could expect the breathing to keep going, but I managed to ring the boys and summon them back quickly. None of us really knew what to do, so it was a blessing to have our friend there (who had seen hundreds of deaths but never his best friend’s) as we all made our promises to my hubby and told him how loved he was. One of the boys became agitated about the music still playing on the iPod, and said it was disrespectful. I told him that Daddy loved music and would probably be enjoying listening to it. In fact, it was Dean Friedman’s Lucky Stars. I made a mental note to remember. I wondered if that was an appropriate song for his life to fade out on, but he did like Dean Friedman. He’d seen him play at the Edinburgh Festival a couple of years ago, and the audience had all sung the girl’s part. I remember him telling me. He’d had a great time. Yes. OK, Lucky Stars was a good song, and I supposed the title was apt. Despite everything, he had been very lucky in many ways, I thought, but then an internal monologue of panic began:

It isn’t really about being lucky at all, though, is it? Isn’t it about a breakup? Not sure. It’s a bit inappropriate if it is. Oh, bollocks. Perhaps I should listen more carefully to the words, just in case. Shame it’s not Ariel. He loves Ariel. Maybe I should see if I can quickly find it. Shit, it’s still on shuffle. 8,493 songs, and I haven’t a clue how to use Search on this bastard thing. Does this one end or fade? Thank fuck – yes, it ends. Don’t want to play “fade out roulette” at this fairly critical point in all our lives.

It ended. I quickly pressed Stop, in case Agadoo came on, or the theme tune from Blockbusters. My hands were shaking. Then, we sort of waited. For a very long time – half an hour or more. We weren’t counting. He kept breathing. We kept talking, and promising, and wishing. The breaths came far less frequently. Then, he stopped.

Our boys were brilliant. They kissed their Daddy, and stroked his face, even after he’d died. One went to our home office and came back with my husband’s business card which he placed in his grey, waxy hand. I don’t really know why. He just did what he had to do. My husband was useless at giving out business cards – perhaps that’s why there were so many left. His best friend organised the practical things such as telephoning the undertaker, and letting Marie Curie know not to bother coming after all. He asked a colleague to come and certify the death – something he’d done a hundred times before for other people, but he couldn’t bring himself to do so for his best friend of over 30 years. I don’t know what certifying a death involves, but I’m guessing lifting eyelids and some such, and I wouldn’t have wanted to do that either. My husband had the most beautiful piercing blue eyes that winked and danced, and we loved them, but they would be glassy and empty by now, and we all knew it.

As had been planned the day before, some dear friends came round to take the boys to drama at 6pm, and we realised that time had stood still. The boys were holding their Daddy’s hand at the time we should have been putting the dinner in the oven. Our littlest twin asked if they could have the night off drama and order a Domino’s, and it didn’t seem a lot to ask for a ten year old kid who’d just come back from school to see his beloved father pass away. There were pizza menus and doctors and telephone numbers for undertakers being banded about, and then the vicar turned up full of apologies but he’d been in Wigan all day and only just seen my text message. He was so sorry. He and my husband were friends. He blessed his body and we said a prayer together, even though by then I knew that my husband had long since left the room, and so did he.

The undertakers came, and quietly began to do what they needed to do. I left the room, and started to make phone calls to relatives. There was a list of people in a vague order of importance, and two hungry children, and I needed to keep the conversations short as there were another twenty people yet to ring, but everyone needed a good cry and I didn’t have the heart to rush them. Even after several calls, I’d failed to master the technique. Words like “peaceful” and “blessing” were used as the doorbell kept ringing and the hallway turned into Piccadilly Circus with doctors and undertakers and small boys and friends. I laid the kitchen table. Someone poured me a glass of wine, I think. As my husband was being loaded into the back of the private ambulance, the Domino’s guy crossed paths with him on the driveway. We’d swapped the love of our lives for a large Margarita and a Veggie Volcano.

As the jalapeños burned my cardboard tongue, I walked into the sitting room and stripped my husband’s empty bed. I found his discarded business card on the carpet. I thought, don’t you know who he is? I loaded the washing machine, just as I always did, several times a day. Life carried on for the rest of us, as it always does, but in a completely new direction. Even now, we’re still picking our way through whatever our new “new normal” is. The only thing that isn’t “normal” is no longer having him here by our side.

Love Fanny x

Ariel, which I found in his record collection, along with Lydia. But not Lucky Stars.